‘Archaeology of Gulag’, or A brief story about our expeditions

Why do we organize expeditions to abandoned Gulag camps? What do these trips bring? What specific conclusions can they help us reach? We attempt to answer those questions in the following article, which is an abbreviated, popularising version of an academic text in the book of Archaeology of Dictatorship published in 2020 by the Oxford-based British Archaeological Reports.

Introduction

It may seem to some that archaeologists have devoted their lives to seeking out valuable goods. However, the reality is utterly different – they are very far removed from the work of ‘treasure hunters’. Their primary interest is (or ought to be) to know better and understand the past human world; they examine not only ‘ancient civilizations’ but also the period of the 20th and 21st century. To do this, they use the so-called ‘archaeological record’, meaning non-written evidence of the period in question. This evidence chiefly concerns artefacts which are, simply put, human creations of any kind – from the most ordinary items to the extraordinarily sophisticated ones. But it also includes human settlements, fields, production areas, or the appearance of the contemporary landscape. Therefore, it does not mean that artefacts are exclusively found underground; a considerable volume of the human activities’ remains are still on the surface and can thus be (relatively) easily documented, even without ‘digging’.

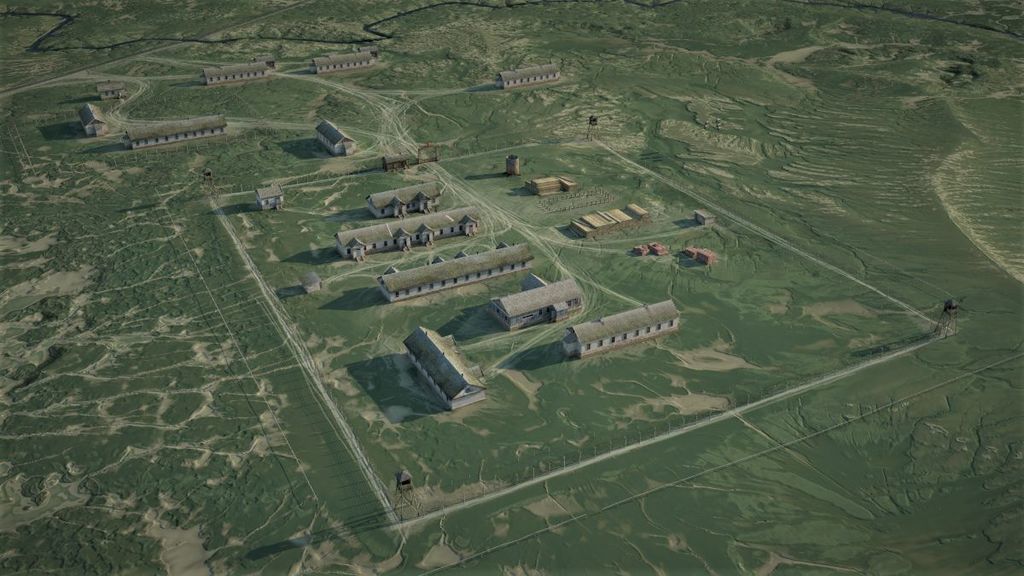

This is just the case with the correctional labour camps spread around the extensive territory of the former Soviet Union that were part of the giant Gulag system – a penal element of the Communist regime’s repressive apparatus. The camp remnants represent unique archaeological sites; they are practically entrance-free museums, time capsules that still preserve an exceptional testimony to one of the most tragic chapters in human history.

The full text of the article is available here.